How’s it Hanging?

- Duration of Activity: 08/07/2023 - 30/09/2023

השאלה ״מה קורה, גבר?״ היא אחת מברכות השלום המקובלות ביותר במרחב הגברי הישראלי היומיומי; היא משדרת אכפתיות, אמפתיה, רצון לקרבה גברית. הטון שבו השאלה נשאלת מרמז על העתיד לבוא – האם זו פגישה חברית? האם זה רגע לפני אלימות מתלקחת?

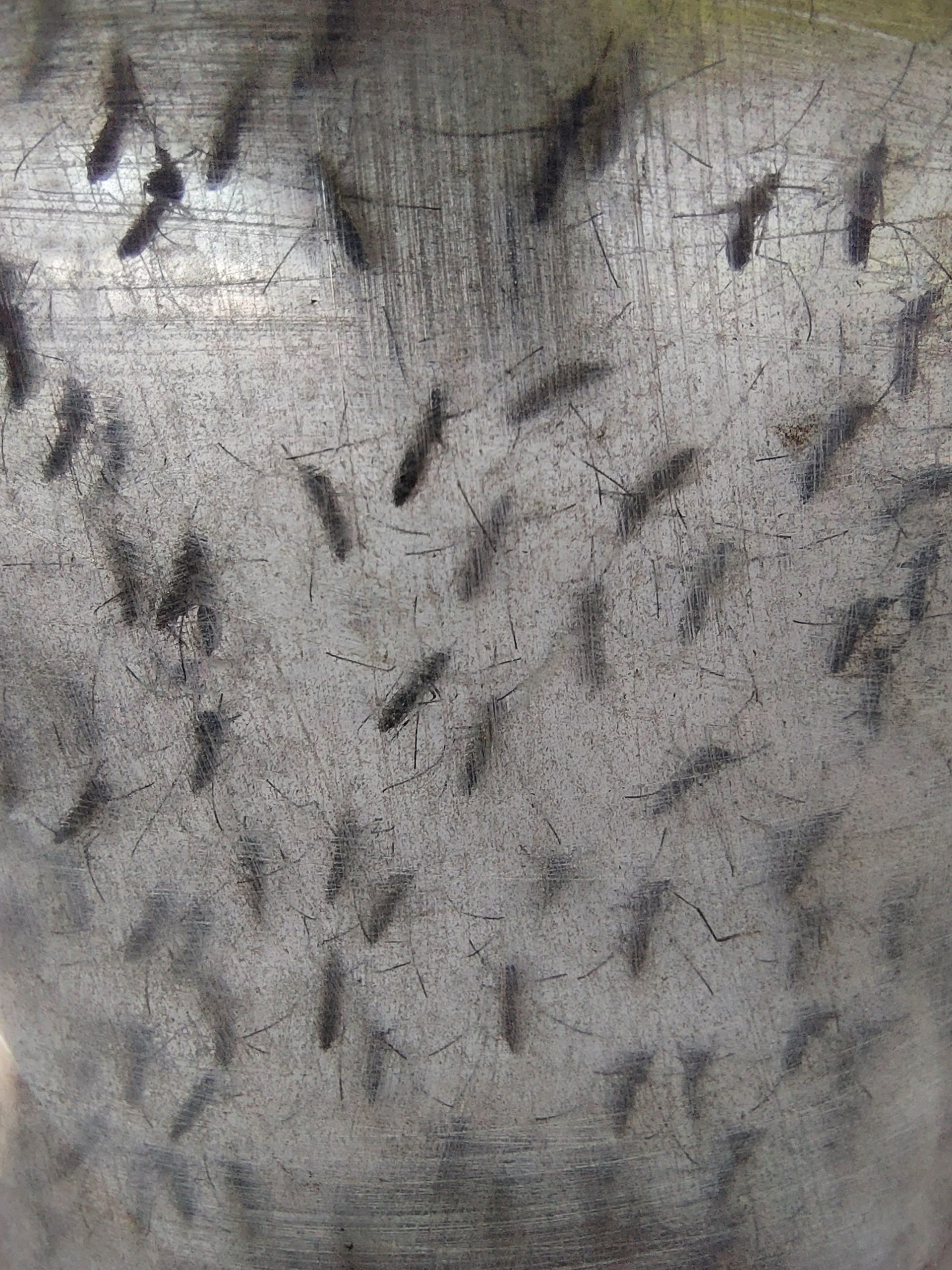

אנרגיה של יצירה משתנה עם הגיל. בשנות העשרים היא חזקה ומתפרצת, ועם השנים היא משנה את צורתה והופכת לרכה יותר. התערוכה הקבוצתית באה לחקור את המרחב היצירתי, מה מניע את הרצון ליצור והאם האנרגיה הזאת משתנה עם הגיל. אוצרות ומעשה אמנות הם מהלך אישי שמגיע מהגוף וחוזר אל הגוף ותמיד מתוך נקודת מבט אישית הקשורה לתהליכים הפיזיים והנפשיים שעוברים על האמן/אוצר. הבחירה לעבוד דווקא עם גברים נובעת מרצון לחקור תהליכים פנימיים שאני כגבר עובר ולבחון האם אמנים אחרים חווים תהליכים דומים. התערוכה מאפשרת להישיר מבט אל מופעים שונים של אגרסיביות ואלימות שהם כנראה חלק בלתי נפרד מהמרחב הגברי. התערוכה איננה רק חגיגה של מרחב גברי נעים ובטוח, היא מביאה לידי ביטוי גם את הצדדים הפחות נעימים של המרחב הגברי: אלימות, מציצנות, כוחנות, השפלה, מתוך מחשבה שכל פעולה אלימה פוגעת בהכרח גם במבצע הפעולה. המרחב הגברי הוא מרחב של קודים שעוברים מאב לבן, אני לומד מאבי איך להיות גבר, איזה תפקיד הוא ממלא ואיך הוא מתנהל בעולם. עם דמות האב הזו אני מייצר מערכות יחסים. דמות האב מסתובבת ברחבי התערוכה, כמו צופה בבנה ההולך וגודל ותופס לעצמו מקום חדש במרחב.

בשנים האחרונות התפתחה פרקטיקה של מעגלי גברים – מרחב סגור שבו גברים יכולים לחלוק זה עם זה את הדברים שמעסיקים אותם. זהו מרחב בטוח של הזדהות, של פירוק ושל בניה מחדש של ערכים כגון חברות, הישגיות ומיניות, של התמודדות עם משברים ושל מציאת הדרך הנכונה לחיות כגבר במאה ה-21. התערוכה מייצרת מעין מעגל גברים כזה, שמאפשר להיות גבר – על האתגרים השונים הכרוכים בכך. התבוננת בתערוכה כבמעגל גברים מזמינה את הצופה להציץ לעולם המורכב של הגבריות בימינו. אין מדובר בגעגוע לעולם גברי שנעלם או במהלך כוחני שמבקש לנכס או להחזיר דבר מה שאבד, כי אם בהבנה שהגבריות מבקשת מקום חדש תחת השמש. הגבריות מחפשת להיות מוארת ומכילה, לבדוק את עצמה מחדש, להיות יותר ממה שאנחנו חושבים שהיא יכולה להיות. את עבודות האמנות בתערוכה אפשר לקרוא ככתב סתרים, שדרכו אפשר להתחיל ולהבין מה היא אותה גבריות חדשה וחמקמקה ואיך היא משתנה במהלך החיים. טווח הגילאים המציגים בתערוכה רחב מאוד, מאמנים בשנות העשרים לחייהם ועד לאמנים שכבר אינם איתנו, והעבודות המוצגות נוצרו בתקופות שונות, המוקדמות ביותר נוצרו בשלהי שנות ה-90 והחדשות ביותר נוצרו במיוחד לתערוכה.

אוצר:

מאיר טאטי