Move Along

- Duration of Activity: 2/07/2022

A white canvas, a burst of cotton thread spun by hand, in an Ethiopian traditional technique. While weaving in Ethiopia was preserved for men, spinning was entrusted to women; knowledge that passed from generation to generation, from mother to daughter, through observation and practice, through the body, through the senses. In Israel, this useful knowledge has been lost. Women no longer spin. Men no longer weave. I hold the white cone softly in my hand. It trembles from the excess movement I create in it—a gentle movement of skilled hands, of women who, while spinning, compose and unravel the everyday through conversation.

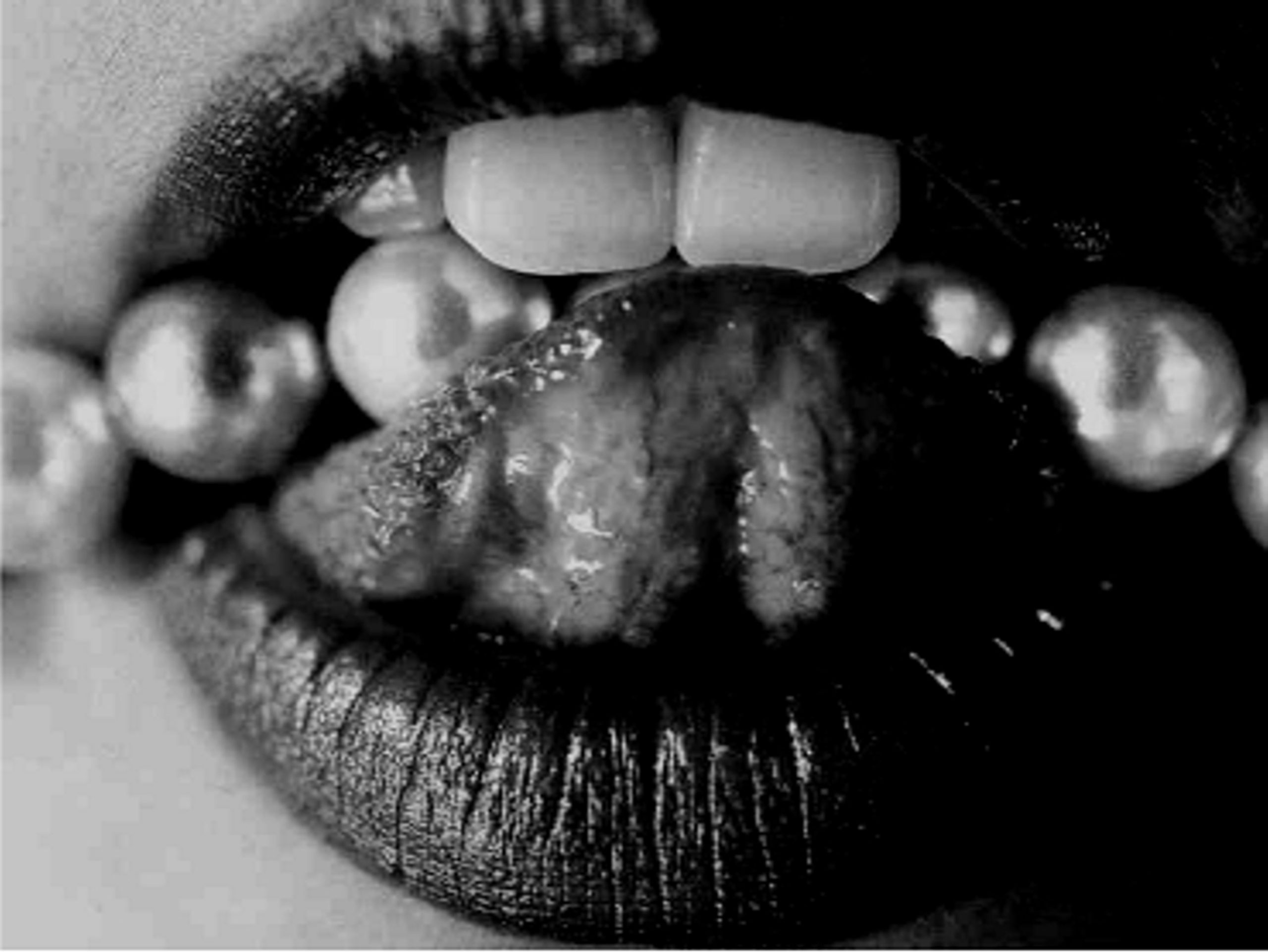

What traces does movement leave in material? How can we extract the story of movement from the space it has vacated? What tribute is created from the encounter between movement and absence? These questions are the starting points of “Raw Movement,” an exhibition that seeks the traces and signs left by movement in space, in material, in experience.

The movement and its traces are central to each of the works presented in the exhibition—and they are also the thread that connects them. The exhibition invites us to contemplate the world through a kinetic perspective, generated by movement—a movement of people, of knowledge, of tradition—and through it, to understand the different works and the relationships between them.

Movement in the exhibition has a concrete connection; the signs and traces are those of human movement, of a tangible body, of human knowledge, of social occurrence in material and space. These spaces contain remnants (real or imagined) that remain after they have been vacated by human presence. The remnants tell the story of the people who passed through them. Vacating is not absolute or final; sometimes it is momentary itself; a pause between movements.”

curator:

Avital Barak

artists:

May Zarhi, Gaston Zvi Itzkovits, Alma Itzhaky, Talia Hoffman, Nardin Saruji, Tamar Geter, Yoram Blumenkranz, Ela Haitham, Dan Robert Lahiani, Michal Samma and Noa Dar.