Irregular Objects – A pavilion by CDA at the Gwangju Bienniale

Irregular Objects is a group exhibition about the nature of objects in our world and our relationship with them. This collection of video and installation works explores objects of different sorts: unseen, virtual, politically charged, out-of-this-world objects and objects that act differently than expected.

What is the nature of our relation to objects? Do we understand objects differently today than we did before? Can there be a new kind of object that could not exist before? What is art’s role regarding unique objects? These are some of the questions explored by the works in the exhibition.

‘Irregular objects’ is a geometrical term used to describe objects that do not have a symmetrical or regular shape – unique objects that lack a repeating pattern or symmetry in their structure or form. Irregular objects, such as rocks and crystals, are found in nature, but irregular objects can also be man-made. In the exhibition, this irregularity refers to objects that take a unique position in the world through relationships with human beings in general or specific groups; these objects can be used as a medium to create dynamics or as a point of struggle, as powerful symbols or religious, deeply meaningful artifacts. The works on display challenge us to consider the role of these objects in shaping our perceptions of ourselves and others, and how they facilitate or hinder communication between different groups. They invite us to reflect on the ways we use objects or are manipulated through them.

The exhibition exposes our different relationships with objects. We often humanize objects to make them relatable, charge them with spiritual or religious meaning, and use them to create a collective idea. For example, Assaf Evron’s installation reconstructs a pre-historic worship site made of stones that are arranged in a simple form of two figures – leopards; or Ruth Patir’s video, where she animates ancient female fertility figurines in a movement that defies their original form.

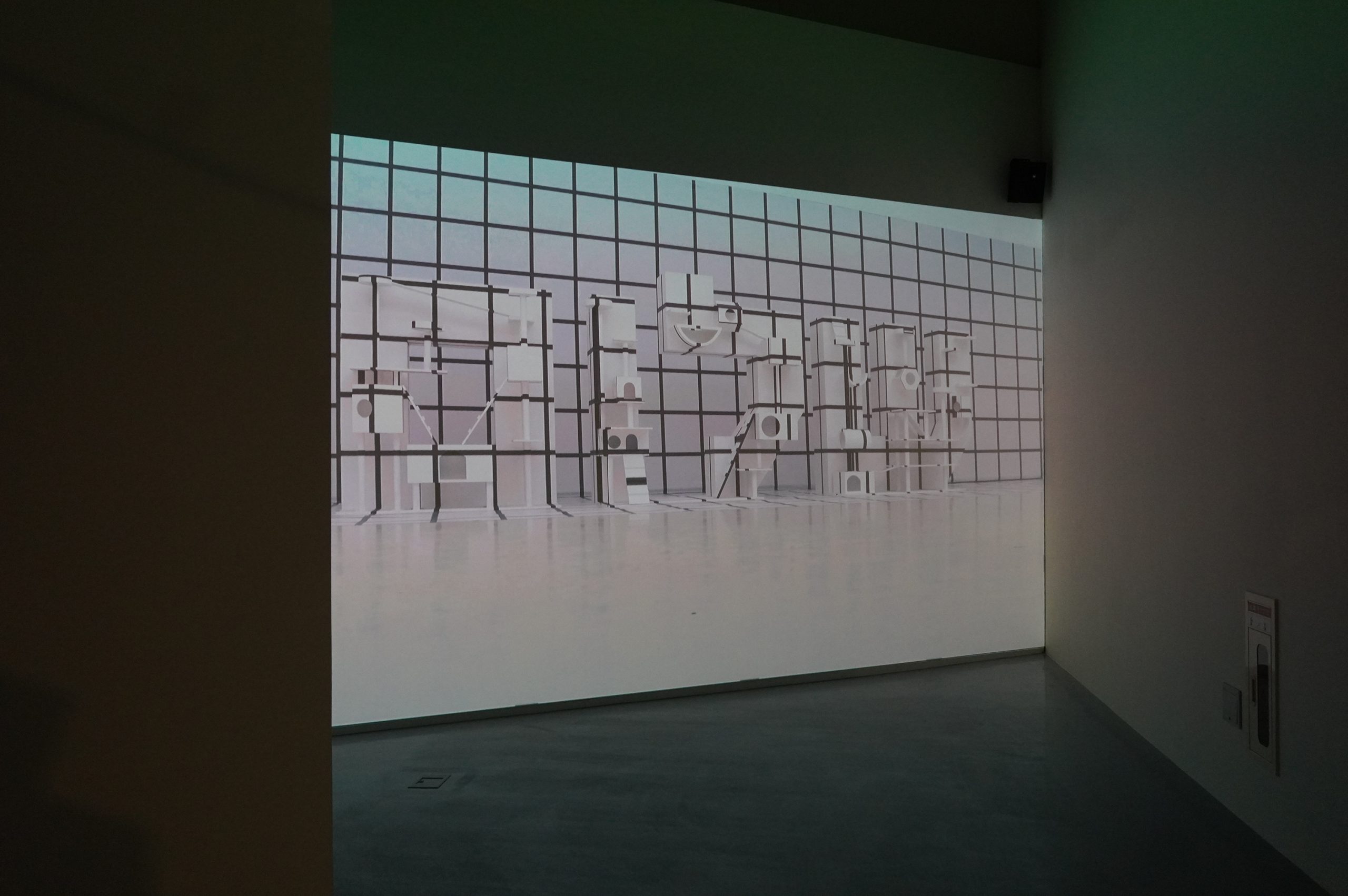

The act of animating objects and bringing them to life, which is fundamental to the human-object relationship, recurs in different ways throughout the exhibition. Roee Rosen’s ‘The Buried Alive Group’ performs rituals designed to breathe life into commodities and act through them. The chants recount the life story of the artifact – a Murphey Richards Iron, for example – how it was created within a specific historical and economic context and how it is linked to people’s life and death. Living objects can also be found in Alona Rodeh’s work. In this video she generates an unpopulated world where independent machines and objects are responsible for their own life and death. In Shachar Freddy Kislev’s whimsical yet poetic work, we discover an object’s possible relation to a living organism when a video that begins as a semi-scientific film about mitosis turns out to be something completely different.

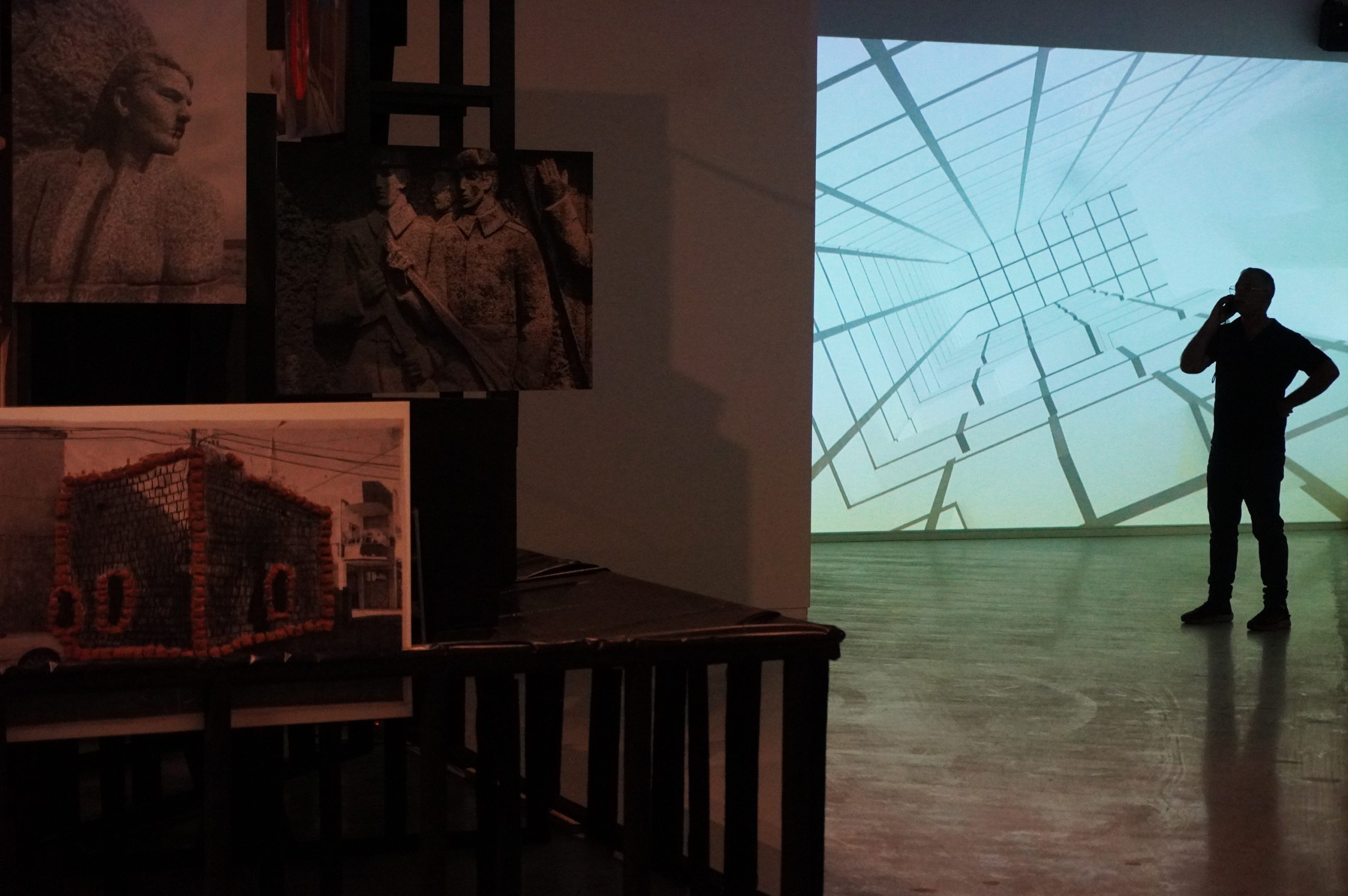

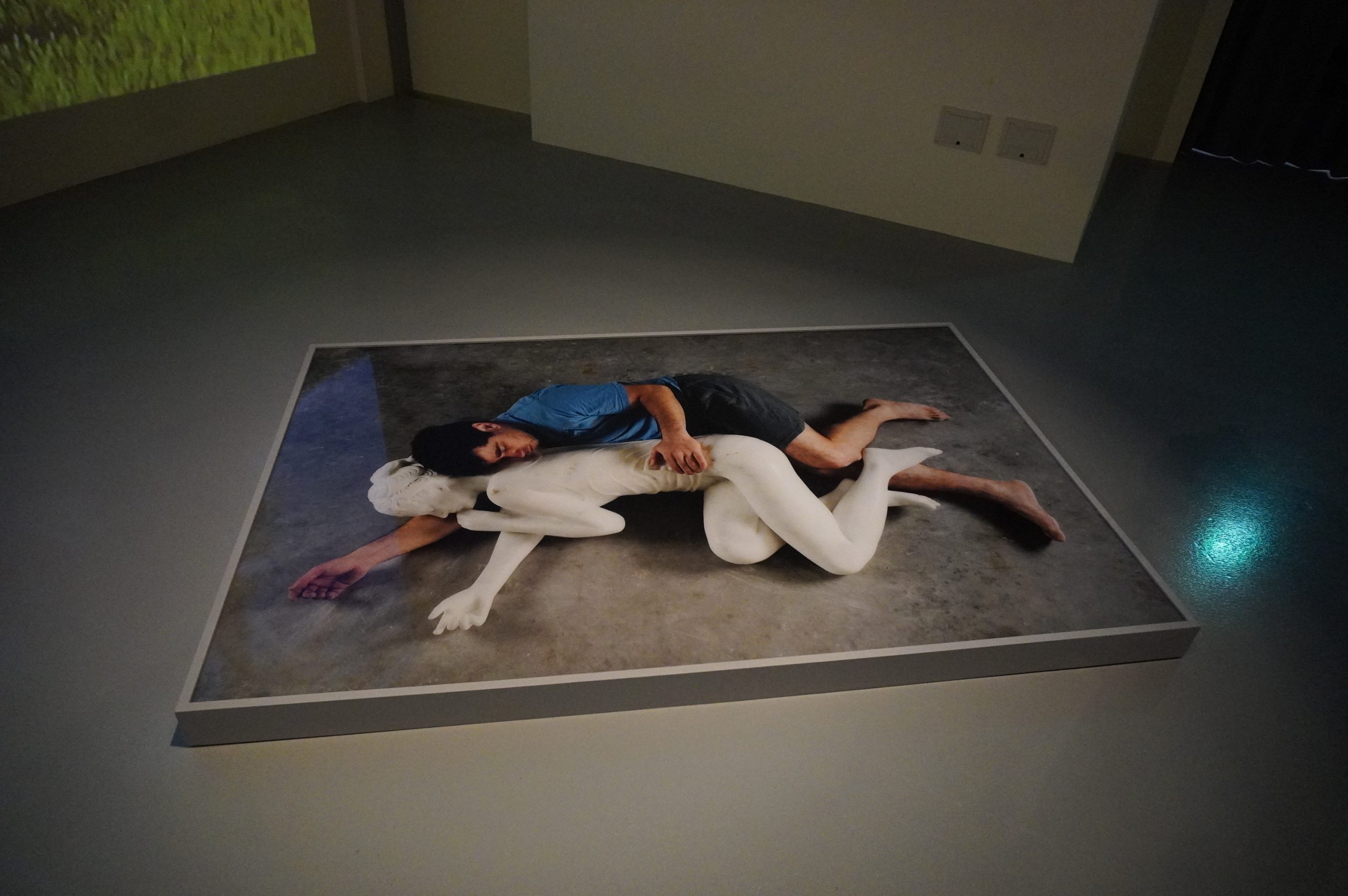

Since time immemorial, objects have been used to signify the link between the living and the dead, like the personal belongings left behind with one’s passing, or monuments designed to commemorate disasters, wars, or prominent figures. Yochai Avrahami’s installation explores images of monuments and how they fall apart and transform, exploring how trauma can be handled over time. In contrast, Zohar Gotesman’s work includes a photograph of a marble sculpture a woman lying down, with him lying next to it, embracing it, as if time stood still, forever preserving the life in the image.

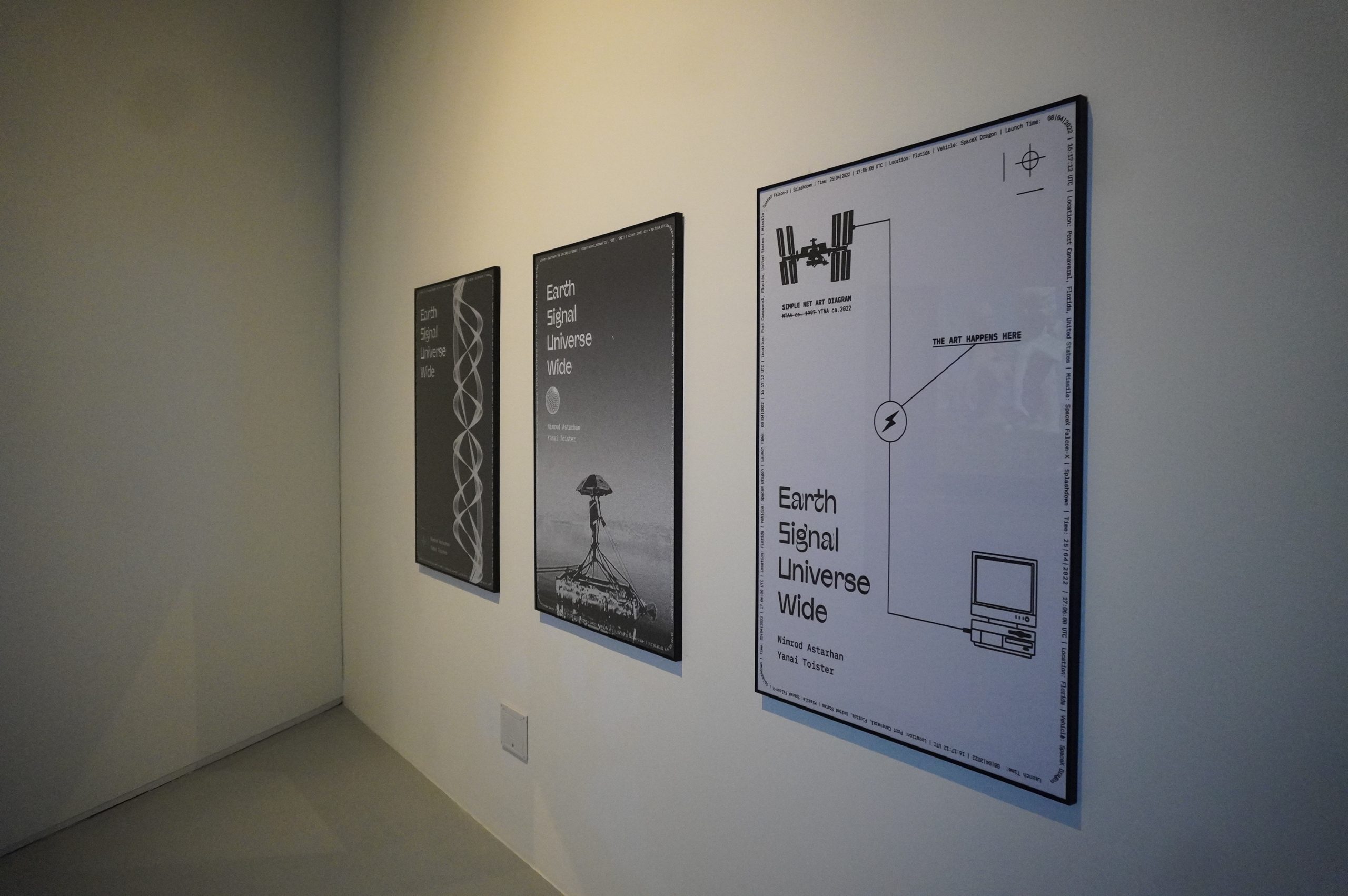

The material aspect of objects is explored in a series of works that exist in space and challenge the very physicality of the object. In Ezra Orion’s 1992 work, a sequence of laser beams was launched into space from different locations on Earth, creating a light object forever moving away from humanity. This conceptual object can never be seen in its entirety. In 2022, Yanai Toister and Nimrod Astarhan created a sculpture using sound waves, alluding to Orion’s work. The invisible sculpture, which can only be seen through imaging, was launched as signals from the international space station (ISS) during the Rakia Mission. The sculpture form is derived from its constant expansion and encounter with other celestial bodies. Another work realized during that mission is Liat Segal and Yasmin Meroz’s ‘impossible object’. This sculpture can only fully exist in zero gravity, so it could manifest at the space station in a way that could never have existed on Earth.

The living world appears in two works in ways that expand the connection between humankind and the world. In Yael Frank’s work, we watch cats wandering on and around an architectural object that shapes the Hebrew word ‘Shalom’ (lit. ‘peace’). However, while we charge its form with cultural and political meaning, the cats are indifferent; they inhabit this environment, climbing, jumping, and sleeping. Unconcerned with the meanings people project onto things, they exercise an unmediated relationship with the object. In Daniel Meir’s sound installation, the object is the world, and the work presents it through different organisms that experience it and in ways we are incapable of perceiving.

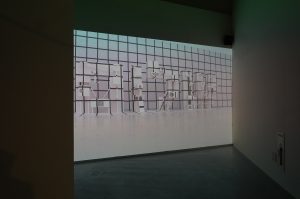

One hidden aspect of the exhibition emerges with the realization that in contrast to the three-dimensionality and materiality that define real-world objects, the exhibition actually consists of abstract images that are laid or hung flat. In a sense, this aspect, which initially resulted from technical restrictions, represents the impossible relationship between human beings and objects. It highlights our one-dimensional connection to objects, defined by how we use them and their impenetrability. The exhibition invites us to observe the object as a concept so we can notice the objects around us and how we use them to mediate our connection to our fellow humans.

Curator:

Udi Edelman

Artists:

Yochai Avrahami, Assaf Evron, Yael Frank, Shachar Freddy Kislev, Zohar Gotesman, Daniel Meir, Ezra Orion, Ruth Patir, Alona Rodeh, Roee Rosen, Liat Segal and Yasmine Meroz, Yanai Toister and Nimrod Astarhan